A Failed Project Attempt – Spring Festival "Fun for Seven Days" (Not Really)

Inspiration

It all started on the high-speed train home for the Lunar New Year. I came across this article on Zhihu: Running Go Programs on Bare Metal. The gist was to take over Go programs’system calls and interrupts by re-implementing the system interface. Such an idea struck me as really fascinating! The author went a step further, building an x86 OS in Go: eggos—remarkably complete. By deeply modifying the Go runtime from the bottom up, user programs are totally unaware anything is different, so third-party Go libraries just work out of the box. The author even implemented a TCP/IP stack, allowing some networking libraries to work straight away. Reading it, I felt a rush of excitement.

I started searching for prior art and discovered that this concept had actually been proposed quite some time ago. For instance, at OSDI 2018, there was a paper analyzing the pros and cons of using high-level languages to implement operating systems—slides here. Plus there are other implementations from recent years, such as gopher-os, a proof-of-concept kernel meant to show the feasibility of building an OS in Go. There’s even a PhD project from MIT called Biscuit, which hacks the compiler to target bare metal. This one is more feature-complete and implements parts of the POSIX interface, to the point where you can run Redis and Nginx on it.

While combing through research materials, I noticed they all shared a trait: they’re based on the x86 architecture. Previously, I’d written a small kernel in C for RISC-V. The RISC-V instruction set and mechanisms are refreshingly straightforward and a joy to work with. So I thought: why not try implementing a RISC-V OS in Go?

Once I had the idea, I was eager to get started—as soon as I got home, I dove straight in.

Let’s Do This!

One of the most important steps in a project is naming it (just kidding).

Still, I thought up a fantastic name right from the start: goose.

Brilliant, right?

Go natively supports cross-compilation to RISC-V 64-bit executables—awesome! Just prefix your go build command with GOOS=linux GOARCH=riscv64 and you’re good to go. Couldn’t be easier.

For the VM, as usual, I went with QEMU, running on a virt platform. The memory layout for virt: addresses above 0x80000000 are physical memory; below that is the MMIO region (basically, device memory is mapped here, so operating on memory in this region interacts with the device). At boot, virt sets the PC to 0x80000000.

However, a normal compiled Go executable runs in user mode virtual addresses, with entry points at low addresses (around 0x10000). Luckily, Go provides a linker flag, -T, to specify the starting address of the TEXT section. You can use it to place the code in high memory; with the -E flag, you can also set the entry point. This lets you write a function to take over Go’s boot process (the actual entry isn’t main but a function called _entry, used for early initialization).

But then there’s a major snag: although we can specify the entry function, there’s no way to set its starting address! You can’t place the entry at 0x80000000, so virt might start up to complete gibberish sitting there. If this were C, you’d just write a linker script to set the entry point at the desired address—trivial, one line. But this is Go.

After some research, I stumbled upon this StackOverflow question about using an external linker instead of the built-in one, which would allow custom linker scripts. But after trying it, things didn’t pan out. Go executables contain, besides the usual text, bss, rodata, and data segments, a bunch of their own weird sections—all of which need to be defined in the linker script, making this approach nearly impossible.

So I switched tactics: what if I wrote the entry in C, which loads the Go binary from memory and jumps to it? The Go code’s entry point exists in the ELF file, but once loaded into memory, that info is gone. So my solution is to link the ELF as a binary blob into the data section of the C program, labeling the start and end as _binary_kernel_elf_start and _binary_kernel_elf_end. The C code can find these easily. The C function’s job is simple: parse the ELF, load its segments into the right memory locations, and jump to the ELF entry.

Here’s the assembly code for the boot entry—set up the stack, then jump to C, with the Go kernel ELF in the data section:

.section .text.entry

.globl _start

# Just set SP then jump to main

_start:

la sp, bootstacktop

call bootmain

# Kernel stack for the boot thread is placed in bss at the stack marker

.section .bss.stack

.align 12

.global bootstack

bootstack:

# 16K bytes for the OS boot stack

.space 0x4000

.global bootstacktop

bootstacktop:

.section .data

.globl _binary_kernel_elf_start

.globl _binary_kernel_elf_end

_binary_kernel_elf_start:

.incbin "kernel.elf"

_binary_kernel_elf_end:And here’s the C code for bootmain—just parses the ELF, reads the program headers, loads each segment to the required physical memory location:

void

bootmain()

{

struct elfhdr *elf;

struct proghdr *ph, *eph;

void (*entry)(void);

uchar *pa;

elf = (struct elfhdr *)(_binary_kernel_elf_start);

if (elf->magic != ELF_MAGIC)

return;

ph = (struct proghdr *)((uchar *)elf + elf->phoff);

eph = ph + elf->phnum;

for (; ph < eph; ph++)

{

pa = (uchar *)ph->paddr;

readseg(pa, ph->filesz, ph->off);

if (ph->memsz > ph->filesz)

clearMem(pa + ph->filesz, ph->memsz - ph->filesz);

}

entry = (void (*)(void))(elf->entry);

entry();

void

bootmain()

{

struct elfhdr *elf;

struct proghdr *ph, *eph;

void (*entry)(void);

uchar *pa;

elf = (struct elfhdr *)(_binary_kernel_elf_start);

if (elf->magic != ELF_MAGIC)

return;

ph = (struct proghdr *)((uchar *)elf + elf->phoff);

eph = ph + elf->phnum;

for (; ph < eph; ph++)

{

pa = (uchar *)ph->paddr;

readseg(pa, ph->filesz, ph->off);

if (ph->memsz > ph->filesz)

clearMem(pa + ph->filesz, ph->memsz - ph->filesz);

}

entry = (void (*)(void))(elf->entry);

entry();

}The final entry address comes from the ELF header, so we just jump there.

Go’s entry point is the rt0 function, written in assembly. Go uses PLAN9 assembly, dating back to the ancient Plan9 OS. This syntax supports multiple ISAs, but mysteriously, there’s no official documentation on exactly which instructions are supported for each architecture. There are some x86 examples, but for RV64…it’s all guesswork.

After much trial and error, I managed to write the entry:

#include "textflag.h"

TEXT ·rt0(SB),NOSPLIT|NOFRAME,$0

CALL ·kernelStackTop(SB)

MOV 0(SP), A1

MOV A1, SP

CALL ·kmain(SB)

UNDEF

RETThe syntax is odd… The logic is: call kernelStackTop to get the kernel stack top, set SP to it, then jump to the Go entry—kmain. The only Go file is very barebones:

type stack [16 * 4096]byte

type virtualAddress uintptr

var (

kstack stack

)

//go:nosplit

func (s *stack) top() virtualAddress {

stackTop := uintptr(unsafe.Pointer(&s[0])) + unsafe.Sizeof(*s)

// 16-byte alignment

stackTop = stackTop &^ 0xf

return virtualAddress(stackTop)

}

//go:nosplit

func kernelStackTop() uint64 {

return uint64(kstack.top())

}

//go:nosplit

func rt0()

//go:nosplit

type stack [16 * 4096]byte

type virtualAddress uintptr

var (

kstack stack

)

//go:nosplit

func (s *stack) top() virtualAddress {

stackTop := uintptr(unsafe.Pointer(&s[0])) + unsafe.Sizeof(*s)

// 16-byte alignment

stackTop = stackTop &^ 0xf

return virtualAddress(stackTop)

}

//go:nosplit

func kernelStackTop() uint64 {

return uint64(kstack.top())

}

//go:nosplit

func rt0()

//go:nosplit

func kmain() {

for {

}

}A stack array is allocated for the kernel stack; kmain does nothing except loop forever. Note every function has the //go:nosplit compiler directive—this stops the compiler from inserting stack overflow checks, but also, crucially, prevents it from inserting GC checkpoints. If GC runs now, on this bare metal system, it’d be disastrous (of course, you shouldn’t run GC in the kernel anyway; it’s for user space heaps).

Now the Makefile can look like this:

Image: kernel.elf

$(CC) $(CFLAGS) -fno-pic -O -nostdinc -I. -c boot/boot.c

$(CC) $(CFLAGS) -fno-pic -nostdinc -I. -c boot/boot_header.S

$(LD) $(LDFLAGS) -T image.ld -o Image boot.o boot_header.o

kernel.elf:

GOOS=linux GOARCH=riscv64 go build -o kernel.elf -ldflags '-E goose/kernel.rt0 -T 0x80200000' -gcflags "-N -l" ./kmainkernel.elf compiles the Go ELF, specifying the entry as goose/kernel.rt0 and placing the .text at 0x80200000. Image compiles the entry code above; image.ld sets the entry function in the TEXT section at 0x80000000.

/* Entry point */

ENTRY(_start)

/* Base address */

BASE_ADDRESS = 0x80000000;

SECTIONS

{

. = BASE_ADDRESS;

kernel_start = .;

text_start = .;

.text : {

/* Place entry function first */

*(.text.entry)

/* Link all .text sections here */

*(.text .text.*)

}

...

}Perfect!

I got so absorbed—throughout the Spring Festival, I barely left the house to see relatives, just stuck in my room scouring material or zoning out thinking up solutions. Totally obsessed.

Epic Fail

Dun dun dun!

Once I loaded the kernel and started it up on QEMU, I noticed in the debugger that it was getting stuck during the segment loading phase. So, I checked the ELF produced by go build using readelf, and saw this bizarre thing:

Type Offset VirtAddr PhysAddr

FileSiz MemSiz Flags Align

PHDR 0x0000000000000040 0x00000000801ff040 0x00000000801ff040

0x0000000000000188 0x0000000000000188 R 0x10000

NOTE 0x0000000000000f9c 0x00000000801fff9c 0x00000000801fff9c

0x0000000000000064 0x0000000000000064 R 0x4

LOAD 0xffffffffffff1000 0x00000000801f0000 0x00000000801f0000

0x0000000000063300 0x0000000000063300 R E 0x10000

LOAD 0x0000000000060000 0x0000000080260000 0x0000000080260000

0x000000000006adb8 0x000000000006adb8 R 0x10000

...Notice that in the third segment, the Offset is 0xffffffffffff1000—a staggeringly large number! Offset is where the segment’s contents are stored in the file, measured from its start. But the ELF is only a few dozen KB—how could the offset possibly be so huge? Even in memory, the default virt machine has only 128 MB, so this just breaks everything.

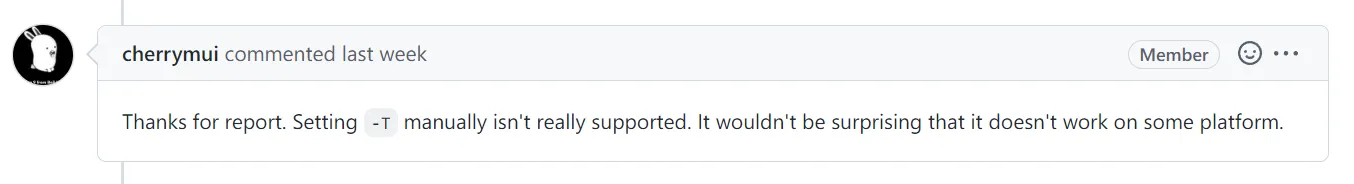

I racked my brain and experimented a bunch. Eventually, I found that simply adding the -T linker flag caused this. But without it, the memory segments are loaded at low addresses—which is MMIO territory! So, I filed an issue on Go’s GitHub: cmd/link: wrong program header offset when cross-compile to riscv64 when setting -T text alignment. The answer I got:

Looks like RV64’s -T support isn’t ready yet…

So, the project has been shelved for now—such a shame, since I’d thought of such a cool name /(ㄒo ㄒ)/. Now I can only hope Go eventually fixes this issue, but, honestly, it doesn’t seem like the team cares much about RV64. Cross-compiling to RV64 only landed in mainline recently…

Feeling a bit salty about it all, I’ve switched to Rust for now!