An Examination of the GFW’s Principles

Technology is innocent.

The Great Firewall (GFW), China’s national internet firewall—often simply called “the wall” or “firewall”—and officially named the Data Cross-border Security Gateway by China’s Cyberspace Administration, is a set of hardware and software systems used by the Chinese government to filter content exiting the country’s international internet connections. — Wikipedia

To effectively combat the GFW, one shouldn’t just focus on which websites are blocked, but must delve into its blocking mechanisms. Knowing that Google is blocked doesn’t directly help you bypass the firewall, but understanding how the GFW blocks Google is critical for selecting and implementing circumvention methods. Therefore, before discussing ways to get around the firewall, one must first thoroughly study the GFW’s blocking principles.

Where is the GFW Located?

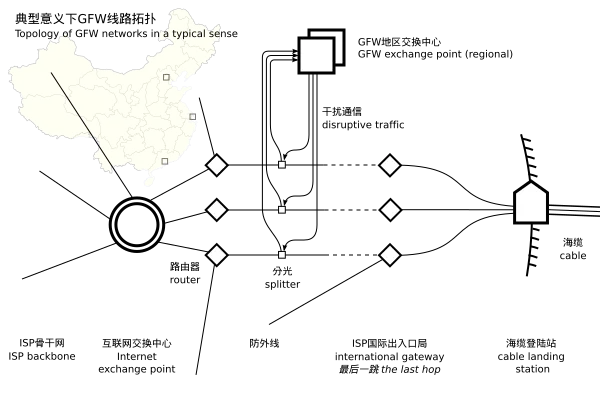

Many might assume that the GFW is deployed right at the outbound gateways, allowing it to directly intercept all outgoing traffic for inspection. However, according to research by gfwrev.blogspot.com, the GFW actually “taps into three international exit points,” using optical splitting technology to replicate all inbound and outbound IP packets to the GFW clusters for inspection. The hypothesized GFW network topology is as follows (image source: gfwrev.blogspot.com):

The GFW aims to couple the heterogeneity of different network lines and has researched various coupling techniques across multiple lines (source: Research on IDS Architecture in High-speed Network Environments). According to the “International Communication Entrance and Exit Bureau Management Measures,” several major ISPs converge at shared international fiber’s landing points, while the Security Management Center (CNNISC) maintains an independent exchange center accessed by individual ISPs. To harmonize differing link specifications for various ISPs, the GFW’s exchange centers must integrate these disparate links, and the different ISPs each branch out side taps to connect with the GFW. Since these connections are primarily fiber optic, this technique is called “side-channel optical splitting.” Experiments reveal that the GFW’s tapping points aren’t necessarily adjacent to the final hop, hence the dashed lines shown in the diagram.

For a more rigorous academic treatment of this, see: Internet Censorship in China: Where Does the Filtering Occur?

Earlier studies (2010) suggested that the GFW disguised itself as a “Virtual Computing Environment Testbed” initiative:

The “Virtual Computing Environment Testbed” was a collaborative project between the National Computer Network Emergency Response Technical Team/Coordination Center of China (CNCERT/CC) and Harbin Institute of Technology (HIT). It leveraged network infrastructure and computing resources spread across CNCERT/CC’s sites in 31 provinces to integrate and utilize distributed autonomous resources, constructing an open, secure, dynamic, and controllable large-scale virtual computing environment test platform to research and validate aggregation and collaboration mechanisms in virtual computing environments.

Based on publicly available papers on this testbed, like A Multi-address Collaborative Job-level Task Scheduling Algorithm in Grid Computing Environments, the 2005 platform setup featured:

| Site | Location | Machine Type | Nodes | Processors per Node | Memory per Node |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNCERT/CC | Beijing | Dawning 4000L | 128 | 2 × Xeon 2.4GHz | 2GB RAM |

| HIT | Harbin | Dawning Server | 32 | 2 × Xeon 2.4GHz | 2GB RAM |

| CNCERT/CC | Shanghai | Beowulf Cluster | 64 | 2 × AMD Athlon 1.5GHz | 2GB RAM |

Of course, these specs were from 2005; the current hardware and software setup of the GFW is much harder to ascertain.

Data Processing

After capturing IP packets, the GFW must decide whether to allow communication between you and your target server to continue. It can’t be too aggressive since a nationwide blockage of foreign websites would defeat its purpose. Only after reconstructing and understanding the IP packet contents does the GFW determine whether to safely block your connection to external servers. This requires reconstructing and analyzing the TCP protocol to assemble a complete byte stream for further inspection of application-layer protocols like HTTP. Then, within the reconstructed application protocol data, it searches for undesirable content and decides on an appropriate response.

To simplify, suppose there are the following three TCP packets:

IP Packet 1: TCP data: Get /inde

IP Packet 2: TCP data: x.html H

IP Packet 3: TCP data: TTP/1.1Reassembly involves joining the data from these IP packets into a single stream: GET /index.html HTTP/1.1. The resulting data might be plain text or encrypted binary protocol data, depending on your communication with the server. The GFW, as an eavesdropper, has to guess the content of your exchange. HTTP is particularly easy to analyze since it’s a standardized and unencrypted protocol. Thus, after reassembly, the GFW can easily identify that you are using HTTP and which website you are visiting.

A key challenge in reassembly is handling the immense traffic volume, explained clearly in this blog. The principle is similar to website load balancers: for a given source and destination, a hash algorithm determines a node. Then all traffic matching that source and destination is routed to that node, where a unidirectional TCP stream can be reconstructed.

To complete the picture, two more notes:

While GFW’s reassembly happens out-of-band via optical splitting, not all GFW devices reside off-path. Some GFW equipment must be deployed in the backbone routing path to engage actively in routing, such as causing intermittent packet loss to Google’s HTTPS traffic. This shows GFW participates in routing some IP traffic.

Reassembly is performed on unidirectional TCP streams. The GFW doesn’t analyze bidirectional conversations fully; it bases decisions on traffic seen in one direction. However, monitoring itself is bidirectional—both domestic-to-international and international-to-domestic traffic are reassembled and analyzed. For the GFW, a single TCP connection is reassembled into two separate byte streams.

Analysis

Analysis is GFW’s second step after stream reassembly. While reassembly focuses on IP, TCP, and UDP protocols, analysis requires understanding the bewildering variety of application protocols, including ones invented by users themselves.

Overall, GFW performs protocol analysis for two distinct but related purposes. The first is to prevent the dissemination of “undesirable” content, such as searching for forbidden keywords on Google. The second is to detect and block circumvention tools.

Regarding how GFW accomplishes the first goal—blocking undesirable content—it primarily inspects plaintext protocols like HTTP and DNS. The general process is:

1. Signature detection

2. Packet parsing

3. Keyword matchingProtocols like HTTP have very obvious signature traits, so step one is straightforward. When GFW identifies an HTTP packet, it parses it according to the HTTP protocol—extracting the request URL from the GET request, for example. This parsed URL is then searched for keywords, such as “Twitter.” Parsing enables more precise blocking and helps avoid false positives; it also saves resources compared to simple full-text matching. For reference, the project liruqi/jjproxy exploited a GFW vulnerability involving HTTP packet parsing—specifically GFW’s failure to handle extra \r\n sequences properly. Google could handle this gracefully, but GFW could not, proving GFW indeed understands protocols before conducting keyword matching. Presumably, keyword matching involves highly efficient regex algorithms.

Currently known protocols that GFW analyzes include:

DNS Protocol

GFW inspects DNS queries sent over UDP port 53. If a queried domain matches certain keywords, DNS hijacking occurs. This matching likely uses regex-like methods rather than simple blacklists given the vast number of subdomains. Supporting evidence:

In March 2010, a Chilean domain registrar’s staff discovered abnormal responses when querying domains like facebook.com, youtube.com, and twitter.com from root servers located in China. As a result, Chinese root server operator Netnod temporarily disconnected from the international internet. Security experts believed this was unrelated to Netnod, but rather caused by Chinese government network modifications.

On January 21, 2014, significant DNS resolution anomalies caused many websites to resolve incorrectly to IP 65.49.2.178, hosted by Hurricane Electric in Fremont, California—a node used by a VPN service provider. Speculation ranged from GFW operator error to the possibility of hackers using this IP as an attack springboard.

On January 2, 2015, GFW’s DNS poisoning method shifted: instead of injecting fixed, blocked IPs, it injected legitimate reachable IPs of overseas sites, triggering DDoS attacks against these servers from China, leading them to block Chinese IPs. In April that year, CNCERT declared the hijacking was due to external attacks.

Source: https://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E9%98%B2%E7%81%AB%E9%95%BF%E5%9F%8E

HTTP Protocol

GFW identifies HTTP traffic and inspects the GET URL and Host fields. If keywords match, it triggers TCP RST packets to terminate the connection.

TLS Protocol

In early TLS versions, parts of the handshake including the server’s certificate were unencrypted. The GFW could sniff this info to determine the visited site. Since TLS 1.3, handshake details after ServerHello (including certificates) are encrypted, generally preventing certificate sniffing.

However, SNI (Server Name Indication), a TLS extension, sends the domain name in plaintext at handshake start to help servers select the correct certificate for hosting multiple HTTPS sites. The GFW still snoops on this plaintext SNI to block connections. Because HTTPS equals HTTP over TLS, detection of HTTPS connections can be categorized as HTTP-level detection.

Note: Since GFW cannot obtain the target domain’s certificate, it cannot decrypt the actual encrypted HTTPS content.

Traffic Feature Recognition

GFW’s second major goal is to block VPNs and circumvention tools. These measures are more aggressive because careless HTTP blocking risks harming normal internet use. Since GFW and the internet coexist symbiotically, it won’t threaten itself. But for protocols almost exclusively used for circumvention, like Tor, detection triggers ruthless blocking. Though precise details remain partially unknown and evolving, here are two illustrative examples showcasing GFW’s technical prowess.

The first example: automatic rejection of Tor connections. GFW tries hard to understand the Tor protocol itself. According to this blog https://blog.torproject.org/blog/knock-knock-knockin-bridges-doors, when connecting from a Chinese IP to a Tor bridge in the US, GFW detects and fingerprints this. Within about 15 minutes, GFW impersonates a client to connect to the suspected bridge using Tor’s protocol. If confirmed, GFW blocks the bridge’s port. Bridges try changing ports, but get blocked again over time. This reveals GFW’s sophisticated capability of pinpointing Tor connections at international edges. Tor’s handshake is notably fingerprintable. Furthermore, it shows GFW’s persistence—posing as clients repeatedly to verify bridges.

The second example: GFW disregards whether encrypted traffic contains sensitive words. Any traffic suspected of being a VPN or commercial circumvention service is subject to blocking. It is (almost certainly) true that GFW has evolved to identify encrypted circumvention traffic via automated machine learning or heuristics.

Clearly, GFW’s recent focus lies heavily on traffic analysis to detect circumvention. Research here is still scant, and a notable feature is that what works well in individual testing may fail at large scale deployment.

Interference Methods

Once GFW classifies a byte stream as “threatening” through protocol analysis, it disrupts communication in one or more of the following ways:

IP Blocking

Usually follows some manual review. No known ways exist for GFW’s devices to instantly block at the detection stage. Typically, GFW first resets active TCP connections with TCP RST packets. After a while, likely with manual intervention, the IP is globally blocked—although no clear timing pattern is evident. Thus, global IP blocks probably require human involvement. This is distinct from partial IP blocking—blocking access for a short time or for a specific user while others still access it. Although the effects are similar (ping failing, etc.), partial and global blocking differ greatly. For example, twitter.com has been blocked globally for years.

Implementation involves inserting invalid routes (blackholes) into backbone router routing tables and letting backbone routers discard packets destined for blocked IPs. Router routing tables are dynamically updated via BGP protocol. GFW maintains a blacklist and announces it via BGP. Domestic backbone routers thus effectively become GFW’s accomplices.

Using traceroute to check globally blocked IPs shows packets are dropped by telecom or Unicom routers before even reaching GFW’s international exit points—demonstrating the BGP blackhole effect.

DNS Hijacking

Another common, usually manually confirmed method. When an undesirable site is identified, its domain is added to the hijack list. Because DNS and IP protocols don’t verify server authority and DNS clients blindly accept the first response, GFW intercepts DNS queries for, say, facebook.com, and races to respond with forged (wrong) answers emulating the queried DNS server before the legitimate response arrives.

TCP Connection Reset

TCP protocol requires connections be terminated immediately upon receiving RST packets. For users this shows as “connection reset.” This is arguably GFW’s primary real-time blocking technique. Most RSTs are conditionally triggered—e.g., when URLs contain sensitive keywords. Many websites are currently affected, including Facebook. Some sites receive unconditional RSTs targeted at specific IP+port combinations, regardless of content—such as HTTPS Wikipedia. At the TCP layer, GFW exploits IPv4’s weakness, whereby it can spoof any IP and send packets pretending to be anyone, tricking clients and servers into believing the RST is genuine from their peer.

Port Blocking

Besides off-path intrusion detection devices tapping into backbone routers via optical splitting (IDS), the routers themselves are weaponized to block ports (Intrusion Prevention System, IPS). Upon detecting threats, the backbone routers can not only send TCP RSTs to interrupt specific connections, but also implement selective blocking measures ranging from port blocking to IP blocking and selective packet drops.

Essentially, backbone routers gain “iptables”-like capabilities (real-time packet inspection at network and transport layers with rule matching). On Cisco routers, this is called ACL Based Forwarding (ABF). Rules propagate synchronously nationwide. If one router blocks your port, all backbone routers with GFW capabilities do likewise.

Port blocks usually target circumvention servers. For example, if an SSH or VPN server is detected, GFW deploys an ACL rule on backbone routers nationwide to block downstream packets from that server’s IP and port—i.e., packets sent from outside China to inside go dropped, while upstream packets still pass.

Servers that change ports after blocking are soon blocked again and may ultimately get IP blocked. This suggests port blocking isn’t automated but uses a blacklist augmented by manual filtering. Supporting this theory, people report port blocks mostly happen during normal business hours.

Reverse Blocking (“Anti-Wall”)

Many VPN providers’ Chinese proxy servers with unusually large international traffic are subject to reverse blocking by GFW during sensitive periods (e.g., National Congress, National Day). Result: foreign servers become unable to reach those proxy IPs. Pings to these domestic servers show connectivity from within China but dropped from abroad. Workarounds include changing IPs or waiting for the sensitive period to pass.

This article is adapted and supplemented from: