6.5840 Lab 1 – MapReduce

Introduction

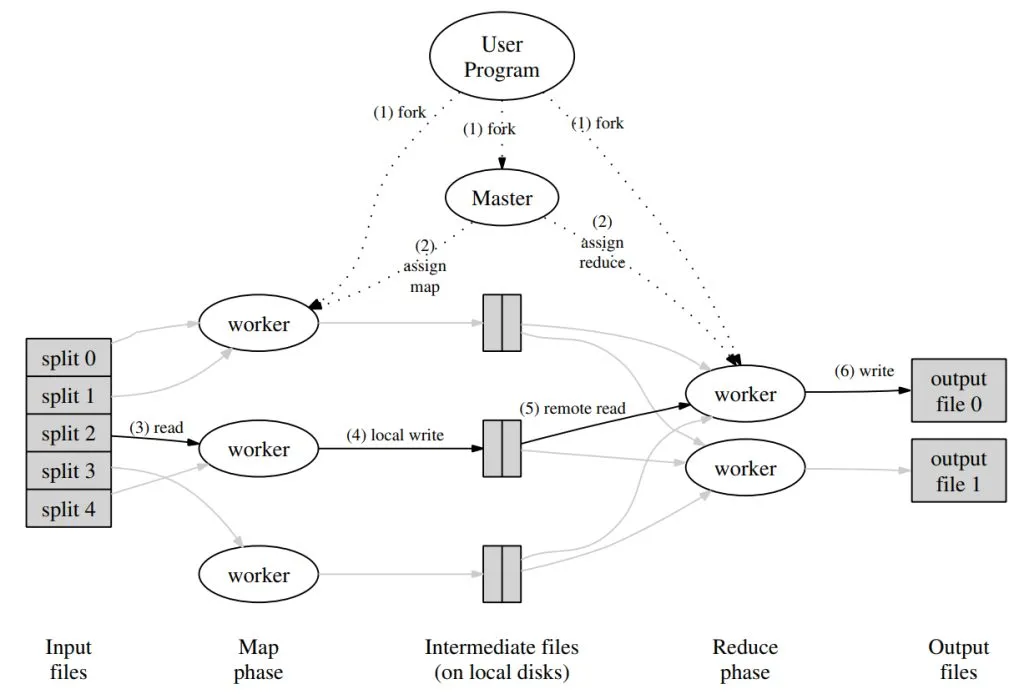

Lab 1 asks you to implement a MapReduce system, which basically consists of two main parts: the master program and the worker program. To be honest, this lab is notorious for weeding out students: first, you need to be fairly comfortable with Go’s RPC and concurrency, and second, you have to really understand how the MapReduce process works. Here’s a tip—the most helpful thing you can do is to study the diagram from the paper relentlessly and pore over the process description below it:

I ended up implementing two versions of this lab, mainly differing in their approach to concurrency control. The initial version used mutex locks, but I later refactored it to use lock-free coordination with Go channels. The lock-free version is a lot cleaner, so that’s what this explanation will focus on.

Lab Walkthrough

Before you begin, the first step is to understand the assignment. All the details are in the instructions: https://pdos.csail.mit.edu/6.824/labs/lab-mr.html. Note: you need to do this lab on Linux, since process communication is based on Unix sockets. In theory, it works on MacOS as well, but there could be some hiccups.

A single-threaded, sequential version of MapReduce is already provided in src/main/mrsequential.go. This code is important—read it through first. It will give you a good overview of the whole process, and you can even copy some of its logic when implementing your parallel version.

The master program’s entry point (for parallel execution) is in main/mrcoordinator.go, and the worker’s is in main/mrworker.go. The files you need to implement are: mr/coordinator.go (code for the master), mr/worker.go (code for the worker), and mr/rpc.go (the RPC data structures). These files govern the master’s logic, the worker side, and the messages exchanged between them.

mrcoordinator calls the MakeCoordinator function from mr/coordinator.go to build the master’s state and start listening for connections via a Unix socket. After returning, the main goroutine repeatedly calls Coordinator.Done to check whether the entire MapReduce job is done—only then does the main goroutine exit. Therefore, MakeCoordinator must not block; you should perform listening etc. in a new goroutine.

mrworker is much simpler. It effectively consists of the main goroutine directly calling the Worker function from mr/worker.go, and you can implement it as a single-threaded loop.

The test script is src/main/test-mr.sh. It runs your framework against two pre-built MapReduce applications: wc and indexer, and verifies their output against the sequential version. It also checks correctness when multiple workers run the same Map or Reduce task in parallel, or even if a worker crashes midway through a task. It typically launches one master process and three worker processes. If you run into hangs, you can find the mrcoordinator PID with ps -A and kill it. Simply hitting ctrl+c may not kill all processes, potentially messing up later tests.

Lastly, read the lab instructions thoroughly, more than once.

Implementation Strategy

Overview

Workers first execute map tasks, generating intermediate files named mr-X-Y, where X is the map task ID and Y is the corresponding reduce task ID. Then, reduce tasks collect all files with Y equal to their reduce ID, read them, perform the reduce operation, and output their result to mr-out-Y.

Master Implementation

Lock-Free Design

For a lock-free implementation and to prevent data races, all modifications to the main data structures are confined to a single scheduling goroutine, which I’ll call the scheduler. When a worker makes an RPC (to get a task or report completion), instead of mutating state directly, the RPC handler packages up the request and sends it via a channel to the scheduler goroutine for processing. Since there are different types of messages, the scheduler manages multiple channels and uses a Go select statement to multiplex between them:

// All structure modifications happen in this goroutine

func (c *Coordinator) schedule() {

for {

select {

case msg := <-c.getTaskChan:

c.getTaskHandler(msg)

case msg := <-c.doneTaskChan:

c.doneTaskHandler(msg)

case msg := <-c.timeoutChan:

c.timeoutHandler(msg)

case msg := <-c.doneCheckChan:

c.doneCheckHandler(msg)

}

}

}Suppose a worker wants to fetch a task via GetTask; the handler looks like this:

func (c *Coordinator) GetTask(_ *GetTaskReq, resp *GetTaskResp) error {

msg := GetTaskMsg{

resp: resp,

ok: make(chan struct{}),

}

c.getTaskChan <- msg

<-msg.ok

return nil

}Here, besides passing resp (note that GetTask requires no request parameters), we provide a chan struct{} called ok, which serves as a completion signal from the scheduler goroutine back to the RPC handler. Once processing is done, the scheduler writes to msg.ok, at which point the RPC handler returns.

Coordinator Data Structures

Here is what the Coordinator struct looks like:

type Coordinator struct {

nMap int

nReduce int

phase TaskPhase

allDone bool

taskTimeOut map[int]time.Time

tasks []*Task

getTaskChan chan GetTaskMsg

doneTaskChan chan DoneTaskMsg

doneCheckChan chan DoneCheckMsg

timeoutChan chan TimeoutMsg

}phasetracks the current stage: since reduce can only start after all map tasks finish,TaskPhaseis either Map or Reduce, andtasksrefers only to jobs for that phase.taskTimeOuttracks the start time of currently running tasks. There is a goroutine that periodically (every second) scans this map for tasks that have been running for over 10 seconds (timed out) and resets them to idle for rescheduling. This scanning also occurs through the scheduler.- The

tasksslice stores all Tasks for the current phase, each with its own status:

type ReduceTask struct {

NMap int

}

type MapTask struct {

FileName string

NReduce int

}

type TaskStatus int

var (

TaskStatus_Idle TaskStatus = 0

TaskStatus_Running TaskStatus = 1

TaskStatus_Finished TaskStatus = 2

)

type Task struct {

TaskId int

MapTask MapTask

ReduceTask ReduceTask

TaskStatus TaskStatus

}Tasks have three possible statuses: idle, running, finished. MapTask and ReduceTask are both included, but only the appropriate one is used depending on the current phase.

Specific Operations

There are four kinds of coordinator operations (reflected by the four channels above).

When a worker requests a task, it may receive one of four task types:

type TaskType int

var (

TaskType_Map TaskType = 0

TaskType_Reduce TaskType = 1

TaskType_Wait TaskType = 2

TaskType_Exit TaskType = 3

)The master first looks for idle tasks in the current phase and returns either a map or reduce task as appropriate. If there are no idle tasks available, two possibilities arise:

- Still in the Map phase: return

TaskType_Wait, asking the worker to wait; later, there will be Reduce tasks to run. - Reduce phase and all done: return

TaskType_Exitto tell the worker to exit.

When a worker reports completion, it tells the master the task type and task ID. The master ignores any jobs not from the current phase, marks the relevant task as finished (regardless of its previous state), and removes its timeout entry. Here’s an example:

func (c *Coordinator) doneTaskHandler(msg DoneTaskMsg) {

req := msg.req

if req.TaskType == TaskType_Map && c.phase == TaskPhase_Reduce {

// Ignore jobs not from the current phase

msg.ok <- struct{}{}

return

}

for _, task := range c.tasks {

if task.TaskId == req.TaskId {

// Mark as finished regardless of previous state

task.TaskStatus = TaskStatus_Finished

break

}

}

// Remove from timeout tracking

delete(c.taskTimeOut, req.TaskId)

allDone := true

for _, task := range c.tasks {

if task.TaskStatus != TaskStatus_Finished {

allDone = false

break

}

}

if allDone {

if c.phase == TaskPhase_Map {

func (c *Coordinator) doneTaskHandler(msg DoneTaskMsg) {

req := msg.req

if req.TaskType == TaskType_Map && c.phase == TaskPhase_Reduce {

// Ignore jobs not from the current phase

msg.ok <- struct{}{}

return

}

for _, task := range c.tasks {

if task.TaskId == req.TaskId {

// Mark as finished regardless of previous state

task.TaskStatus = TaskStatus_Finished

break

}

}

// Remove from timeout tracking

delete(c.taskTimeOut, req.TaskId)

allDone := true

for _, task := range c.tasks {

if task.TaskStatus != TaskStatus_Finished {

allDone = false

break

}

}

if allDone {

if c.phase == TaskPhase_Map {

c.initReducePhase()

} else {

c.allDone = true

}

}

msg.ok <- struct{}{}

}If all reduce tasks are finished, it also sets the allDone flag.

When initializing, the Coordinator launches a goroutine that, once per second, checks for tasks that have timed out and resets them for rescheduling:

func (c *Coordinator) timeoutHandler(msg TimeoutMsg) {

now := time.Now()

for taskId, start := range c.taskTimeOut {

if now.Sub(start).Seconds() > 10 {

for _, task := range c.tasks {

if taskId == task.TaskId {

if task.TaskStatus != TaskStatus_Finished {

task.TaskStatus = TaskStatus_Idle

}

break

}

}

delete(c.taskTimeOut, taskId)

break

}

}

msg.ok <- struct{}{}

return

}Finally, for completeness, the master’s Done method just checks the allDone flag.

Worker

The worker is a single-threaded loop, continuously requesting and executing tasks from the master:

func Worker(mapf func(string, string) []KeyValue,

reducef func(string, []string) string) {

for {

resp := callGetTask()

switch resp.TaskType {

case TaskType_Map:

handleMapTask(resp.Task, mapf)

case TaskType_Reduce:

handleReduceTask(resp.Task, reducef)

case TaskType_Wait:

time.Sleep(time.Second)

case TaskType_Exit:

return

}

}

}Refer to the sequential implementation for examples of how to perform map and reduce. One thing to watch out for: since multiple processes may execute the same task in parallel, or crash midway and leave behind partial files, it’s important not to write output files directly. Instead, create a temporary file (using ioutil.TempFile), write the output there, and rename it to the target filename with os.Rename. This ensures that only complete files remain.